Inside the row tearing the Royal Society of Literature apart

At July’s summer party, as he celebrated having “the greatest number ever of literature’s finest in one room”, Daljit Nagra told the assembled fellows he was “blushing ever so chocolatey”, adding: “And I can say that.”

Six months later, the 200-year-old Royal Society of Literature (RSL) that he chairs is facing its biggest crisis — sparked in part by the fundamental tenet of any writer: I want to say that.

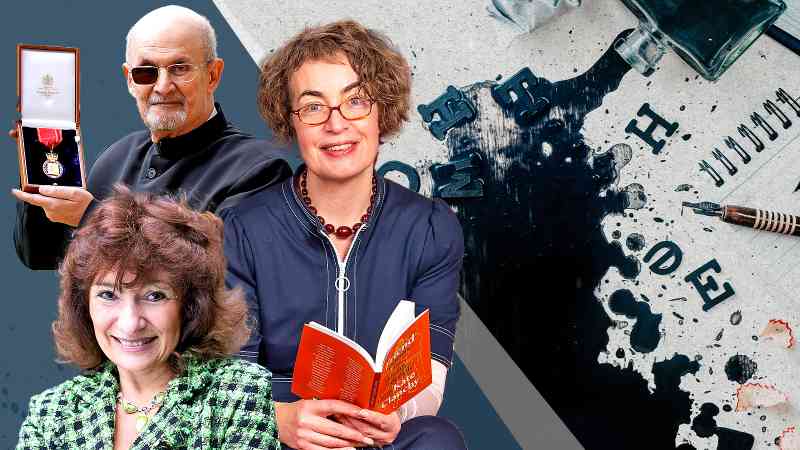

Some of the country’s finest wordsmiths, including former presidents of the society, have spoken to The Times this week about their horror at what has unfolded within the organisation. They say the refusal to take public stands against the attacks on Kate Clanchy and Salman Rushdie, the sacking of Maggie Fergusson, the editor of its annual journal, and the scrapping of this magazine allegedly because of an article mentioning Palestine, have called into question its support for a writer’s right to freedom of expression.

Many of these fellows of the society are considering resigning; some already have.

Among them are:

• Dame Marina Warner, the president from 2017 until 2021, who said she was “incensed” at the “reprehensible” behaviour of the society’s management, which had launched an “autocratic takeover”.

• Maggie Fergusson, the RSL’s former director and editor of its Review magazine, who has accused it of being “simply, categorically inaccurate” with its explanation about her dismissal before Christmas.

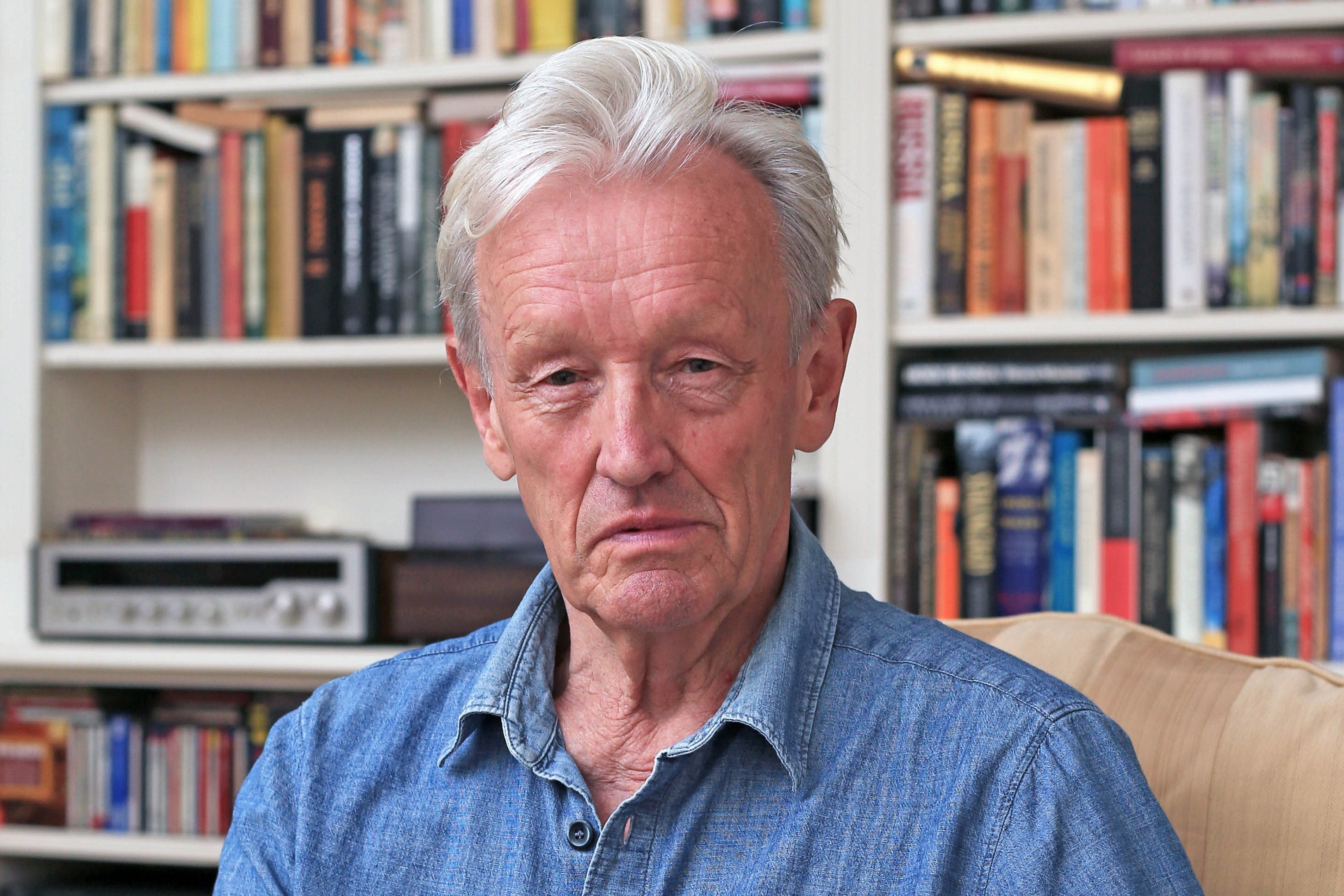

• Colin Thubron, the president before Warner, who has questioned its public explanations about the “cancelling” of its annual magazine which, sources attest, was due to “sensitivities” over a piece mentioning Palestine.

• Lisa Appignanesi, chairwoman of the society until 2021, who said the institution had been brought into disrepute by censorious, autocratic management.

The sacking of Fergusson, an acclaimed biographer with more than 30 years’ service to the society, has catalysed anger, but the roots go deeper.

“There were two major clashes when I was president,” Dame Marina Warner said this week. “The first was that they would not make a stand about the attacks on Clanchy, some sort of defence for all writers facing these social media attacks.”

Clanchy is a teacher and Orwell prize-winning writer who was dropped by her publisher and widely abused on social media after being accused of using racial stereotypes to describe some of her students who, it should be said, continued to support her.

Last year she resigned as a society fellow, in part because it had bestowed a fellowship on one of her online critics. Sir Philip Pullman was forced out of his position as president of the Society of Authors because of his support for Clanchy.

“The second thing was that they would not post a pledge of support for Rushdie after he had been nearly murdered,” Warner continued. “They said it might give offence.” Both Warner and Lisa Appignanesi said they were never told — by the society’s small management team, or secretariat — who might be offended.

And then came December 2023. On the sixth of the month, Fergusson was told by the society’s director, Molly Rosenberg, that this annual edition of Review — which was on the verge of being printed — would be her last.

The society said this week that Fergusson knew before “taking on the editing of this edition” that this would be her last.

Fergusson told The Times: “That is simply categorically inaccurate.”

Anne Chisholm, the former chairwoman and a current vice-president of the society, said she spoke to Fergusson after this “last conversation with Molly … there was no doubt at all that she was reeling from having just been fired”.

This was also when Rosenberg announced that that year’s Review, a bumper annual magazine packed with commissioned articles, was to be scrapped.

The Times has been told by sources that this was because of one article which mentioned a visit to last year’s Palestine Festival of Literature and of the writer’s “observations” about the “Israeli war machine”.

The society has repeatedly denied this and said this week that the article would be “printed in full” in the “postponed” edition.

In an email seen by The Times, Thubron said after a visit to see Rosenberg in December to ask about the Review: “It would be accurate to say that I remained (and remain) unconvinced that this [the offending article] was not, at least, a contributing factor, and may have tipped the balance into Molly’s ‘postponement’.”

Jenny Uglow, another former chairwoman, said in an email to the management that the RSL’s “narrative keeps changing” about the “postponement”.

Warner said this week: “They will produce the whole magazine now because the idea of writers practising censorship on themselves is just so horrendous.”

Ruth Scurr, one of the 15 fellows on the ruling council, confirmed that they had not been consulted about the “postponement”.

She said there was a trustee meeting on February 20, which is when she would raise “any concerns I have”.

The society further upset its fellows when, after journalists started asking questions about the “cancelled” article, Nagra, Rosenberg and its head of communications, Catherine Riley, wrote to them all warning not to share “misinformation”.

“It is one of the things that has been reprehensible,” Warner added. “The responses have been to be quiet or else, which is extremely unpleasant and not at all in keeping with the ethos of a fellowship society like the RSL.”

And there are other concerns held by some but not all.

During the tenures of Thubron, Warner and Appignanesi the society began expanding its fellowship in an attempt to diversify and lower the average age.

This has continued with members of the public now nominating writers, whereas previously fellowships were bestowed on those with at least two acclaimed publications.

Warner’s successor, the Booker prize-winning author Bernadine Evaristo, made clear her plans in an interview with The New Yorker shortly after assuming the presidency. “It’s like you’ve got 200 years of history to counterbalance … so are you going to wait another 200 years or are you going to just speed the process up a bit?”

Not all, however, are happy with this “inclusionary” approach.

Philip Hensher wrote on social media: “Was the RSL really exclusionary until recently? I mean, they elected [VS] Naipaul to a fellowship in 1962 when he was only 30. Some of the writers who have benefited from this widening are, one, expensively educated and privileged, and two, not very good.”

His fellow writer Amanda Craig said this week: “It was something that was a real honour to be made a fellow: you had to have a serious track record of literary publication and achievement.

“I think many people, myself included, feel that although the fellowship was a bit too pale stale and male before, it has become so diluted by younger writers with few books to their name that it is no longer the kind of distinction that it was.”

Evaristo, the president, did not respond to repeated requests for a comment.

The society denied it was run in an “autocratic, dictatorial manner” and said there were “frequent frank and robust discussions between the chair, director and senior management team”.

It said there had been a “number of issues” with the magazine and denied lying over the reasons.

It also defended the broadening of the fellowship, saying: “Of course, taste is subjective and we understand that fellows are not exempt from having opinions on what ‘qualifies’ as great literature.”

“What we do is ensure transparency, inclusivity and fairness in the fellowship process, and commit to championing all kinds of writing to all kinds of readers.”